- Home

- Paul Roscoe

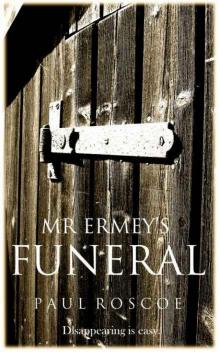

Mr Ermey's Funeral

Mr Ermey's Funeral Read online

Mr Ermey’s Funeral

Paul Roscoe

For Gabrielle

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Copyright

Chapter One

1

Mr Ermey opened his eyes.

Light shone through the window in dusty rays, spotlighting the corner where the Townsends’ television set would normally stand. Removed to make more space, no doubt, but no one was standing over there; everyone was standing over here, right next to him, and all around him. At last, he thought, gazing at the vacant spot, somewhere I can disappear. Without hesitation he began to squeeze his way along the mantelpiece, muttering sorry and excuse me with every shoulder and elbow he brushed past. Then, just as he finally made clear of the solemn scrum that had gathered around him, he felt an awful tugging sensation on his arm, and knew exactly what it meant. Hoping it was not too late, he took a cautious step backwards, but a heavy scraping noise confirmed that whatever ornament had snagged on his suit was no longer resting on the mantelpiece. Wincing, he froze as something large, heavy, and no doubt fragile clattered from the fireplace and exploded on the freshly varnished floorboards. The crash filled the room, swallowing the steady murmur of platitudes with one gulp.

People backed away. Clenched tissue in hand, Mrs Townsend shook a weak fist at the mess and began to wordlessly moan. Her husband dropped to his knees and scuttled across the floor. Mr Ermey watched with queasy fascination as the man weaved through the mourners on all fours, grabbing bits of ornament and stuffing them into his jacket pockets, sharp edges and all. He looked from the man at his feet to the faces that spread out around him, and wondered if there was anything he could say that wouldn’t make things any worse. The idea of opening his mouth and acknowledging this awful scene, even by way of a simple apology, seemed abhorrent.

Maybe you should just go, old man, he thought.

Yes. It was the only sensible option. He would deal with the inevitable jibes in the staff room, but for now his presence could only lead to more discomfort.

Mr Ermey was about to head for the door when, hoping it was not too late, he took a cautious step backwards, turned, and stopped the ornament before it fell from the mantelpiece. A few of the other mourners looked over at him with mild interest, but their eyes soon reverted to the main attraction lying in the centre of the living room. There was no heavy scraping noise, no room-silencing explosion, and no awkward aftermath involving a recently bereaved father crawling on the floor cutting his fingers and ruining his suit. Mr Townsend stood with his wife near the door, their lips making welcoming noises, but their eyes red and distant.

Mr Ermey looked at his hands and felt faintly amazed by – and somewhat proud of – his own reactions. Deliberately, he lowered them to his sides and traced the outline of his wallet through the fine fabric of his right trouser pocket, and traced the outline of his keys in his left. Then he started to gently rap his ring, middle, and index fingers against his wallet three times, until his index finger came to rest solely on the hard surface.

“One,’ he muttered beneath his breath.

One. Everyone is minding their own business.

Three more raps against the wallet, finishing the third set with the middle.

“Two.”

Two. I stopped the ornament before it fell from the mantelpiece, and that’s why everyone is minding their own business.

Two complete raps then finally the ring.

“Three.”

Three. This is a wake. Her wake. I stopped the ornament before it fell from the mantelpiece, and that’s why everyone is minding their own business.

Relief coursed though him as he finished what he privately called his ‘count-check’ with a final flourish of finger-rapping and counting, completing a full finger rap against his wallet for each word whispered.

“One-two, one-two, one, two, three.”

Done for now at least, he finally took a good look at the object he had saved from destruction, and as he did all sense of relief evaporated. As he reached for it, Mr Ermey’s hands began to tremble.

It was not an ornament at all, but one of Mary’s paintings.

2

In a thirty-year teaching career that had seen few really good pupils, Mr Ermey thought Mary Townsend had been that rarest of things: a truly great pupil. This matter had very little to do with his input, however; aside from a few technical pointers, he had elected to step back and give her the space she needed. At first it had been something of a gamble, perhaps, but it had proven to be a wise decision: over the years he had watched her artwork develop at an exponential rate. The painting in his hands marked yet another stage in that development, albeit a final and sadly unfulfilled one. Holding it, he sensed an infinite number of unseen, unrealised achievements slip away from his fingers like a stack of papers lost to the wind.

He gazed at the painting of the old shelter, puzzled.

Typically, Mary had done figures.

So far as he knew this was only her second landscape, her first had been the unfinished exam-piece he’d reluctantly taken down, and even that had had plenty of figures in it. Both paintings had that offhand-accomplished feel only the truly gifted could muster, and both were undeniably better than anything he would ever manage. Already her work exhibited an unstoppable forward motion; each piece captured a sense of the artist going in hard, catching the idea, and then moving beyond it.

What could he do with a talent like that, other than to clap and cheer?

Still, at least he had done that to the best of his ability. Mr Ermey noted the small trademarks of her work he’d encouraged, qualities that, without recognising their worth, he feared she might grow out of: the simplicity of her brushwork, the balance of her palette, and her immaculate, though often unorthodox, composition.

But surely there was something more, something of himself in there? The subtle blending of colour, perhaps, the dynamic use of light and shadow...maybe.

Or maybe not – you’re not fooling anyone, old man.

He sighed loudly through clenched teeth, making a hissing noise.

People shifted; looked over; looked away.

The old shelter, he thought, shaking his head. Throughout the Sixties, Seventies, and Eighties he had seen drawings and painting of St Vincent’s from every angle, but so far as he could recall, no one had ever drawn the old shelter.

Set at the foot of the playground, at the far edge of Tithborough woods, the old shelter no longer served any practical use, if it ever had. The most likely would have been as a bike shed – which he guessed most people assumed it had been, if they ever stopped to think about it – but having inspected it many times, he knew there were no bicycle rails, and no markings in the flagged floor to suggest there ever had been. The old shelter was just a thing, a large, ugly ornament, mistreated by time. If Mary’s painting was to be believed – and he did not doubt its accuracy for one second – large sections of the corrugated roof were missing, and the remaining sections had holes big enough to drop a tennis ball through.

But what had it been designed to shelter in the first place, if not bicycles?

The canopy was long, narrow, and tall; too tall to be of any use against the

rain, and too narrow for people to do much of anything other than stroll beneath. Unless a person was emerging from – or descending into – the woods beyond, Mr Ermey could see no reason to be there.

An image rose in his mind of an indistinct figure – little more than a suggestion of movement and shadow, a glimmer caught in the corner of the eye – appearing and disappearing beneath that surreal canopy. Something there and gone.

Of course. That’s its real form of protection, isn’t it? Kids hang out at the old shelter – pupils, that is – but the teachers never bother. Why? Because there’s no reason to be there, that’s why. It serves no ‘practical use’. Without teachers, the old shelter is like a black hole where pupils can disappear for as long as they like.

As he mulled this over, his focus slipped through the painting, turning it into a soft blur of colour. Mr Ermey blinked, his eyes watering slightly, and the details re-surfaced: thick, twisting strokes made the shelter’s support posts stretch, forming needle-sharp teeth rising from the ground and hanging from the canopy. The shelter was grinning. Fine, rapid lines curled the concrete floor at the edges, drawing the eye deep into the black and oppressive woods beyond. Layered upon this background, Mary had positioned a group of seemingly abstract shapes. One looked like...

Mr Ermey raised the painting to his chin, angling it to the light. The relief of the paint revealed familiar splodges, and he had to fight the laughter that now threatened to burst from his chest.

Mary had painted figures after all, but at some point she’d thought better of the idea and had painted over them. The work was hidden, but only partially so.

Giddy with this new discovery, Mr Ermey scrambled to make sense of the grouping. The best he could tell in this light (despite the strong, yellow shaft that skimmed the shoulders of people standing in the window, casting their elongated shadows on the wall, the room’s overall atmosphere was dull and shaded) was that Mary had partially erased at least four separate characters. The added details were faint and ghostly, almost invisible: a yellow jacket of some kind; a football; a lit cigarette; and a crescent portion of a bicycle wheel edging out from behind one of the supports.

So Mary thought the old shelter had something in common with bike sheds too.

Feeling watched, Mr Ermey looked up: the Townsends’ living room had been granted a fresh intake of mourners, and the little space he occupied was now even smaller. He caught a strong waft of his own aftershave as he realised he was now almost hugging the painting. Peering over someone’s shoulder, he saw a group of schoolchildren, two of which he recognised.

Craig Anderson and Angela Welch stood on the far side of the casket. Craig looked pale and drained – Mr Ermey thought he looked either sick or scared, and concluded that he was quite probably a combination of the two. To his left, Angela fussed with a tissue, her mascara already starting to run.

The other schoolchildren – three boys and a girl – stood before the coffin; with their backs turned, and their bodies in such close proximity to one another, they were impossible to place. He shook his head and watched as Craig and Angela backed away towards the far wall, both pretending to be interested in the contents of a small coffee table. Angela picked up a framed photograph of Mary and examined it. Mr Ermey looked around the room and supposed that, if you didn’t want to make small talk, there was little else to do: framed photos lined the windowsill; innumerable Polaroids were pressed behind large glass mounts; and neat groups of 6 x 4 inch glossies plastered on the walls created impenetrable windows, dark spaces where a pallid girl with long, greasy hair looked out forever.

Was this how they saw her?

The evidence was overwhelming, and it occurred to him that as her Art teacher he had known a side of Mary her family never had, and never would. Perhaps it was a terribly pretentious thing to think, but it was undeniable. Whereas the girl in these photographs looked apathetic and cynical, the girl he had known in Art class was full of intelligence and quiet enthusiasm. He only needed to close his eyes for a moment to remember her that way:

Mr Ermey closed his eyes.

Golden light filters through the treetops, streams across the playing field, and pours in through the large window. It sets her pale skin on fire. Her ponytail falls in a steady twist, brushing against the knotted apron strings tied in the small of her back. Her flushed cheeks are smudged with charcoal dust, and her breath grows ever deeper as she disappears into her work.

Mr Ermey opened his eyes.

Looking at the walls again, feeling the weight of all those miserable, glaring faces, his mental image began to flatten and disappear. Bright spots of wet heat flared beneath his arms and under his chin, where a tender shaving rash was now starting to itch and sting. Trying to avoid his own sensitive flesh, Mr Ermey carefully ran a finger along his shirt collar and tugged at it a little, but it was no use, so he undid his top button and loosened his tie, appearances be damned. The waft of aftershave that came had an acidic undertone that he did not care for.

Instinctively, he took a deep breath, sucking back more perfume, stale air, and dead girl, and then, watching himself in slow motion, watching himself act without thought or real awareness of what he was doing, he replaced the painting to its original, precarious position on the mantel and walked to the door, edging between people, excusing himself in whispers. He exited the living room and entered the hall; things were a good deal cooler there. A few mourners, most notably an attractive woman in a navy blue dress, meditated on photographs hung on the wall, but at least the air tasted fresher out here, lighter. The same sunlight that had revealed the secrets of Mary’s final painting now drenched the narrow space through which he moved. A light breeze drifted in through the open front door, calling him, and Mr Ermey headed slowly towards it, relishing the clean air. At the over-stuffed coat rack, a flock of photo-admirers blocked the way, and he was trying to think of the right way to say: Look, I know you’re mourning and everything, but can I please get past? when the house fell silent. A sharp, businesslike voice invited the gathering to join him in prayer, and a murmur of voices slurred through the living room wall:

“Our Father, who art in heaven...”

Doing the only thing he could, Mr Ermey joined the group at the coat rack – none of which were outwardly indulging in the Lord’s Prayer. For something to do, he craned his neck to glimpse the photographs that fascinated them so.

It was a line of small glossy prints which, running left to right, showed Baby Mary, Toddler Mary, Little Girl Mary, and lastly, Young Woman Mary, the Mary he had come to know. In each shot, tinsel and colourful packages were in evidence. Mr Ermey counted sixteen prints. He mentally added this set, the others in the hallway, and the plethora in the living room and felt somewhat appalled at the extent of the Townsends’ preparation for today. He pictured them digging through sixteen years’ worth of albums, discussing which shots they would display, arguing over the specifics of their grouping and positioning.

Then he noticed something terrible, something in the Christmas photographs.

Mr Ermey moved closer, leaning in over strangers, trying not to brush against them too heavily, trying not to give off too much tainted aftershave. The subject of the last five shots – Young Woman Mary – stared at the camera with dull eyes, looking no different from the girl staring down repeatedly from the living room walls. He ignored these, however, and concentrated on the photographs that had been taken earlier in her life.

The attractive woman in the navy blue dress commented, “She looked different as a little girl didn’t she?” Mr Ermey realised he was pressing slightly against her shoulder, and he edged back, nodding, his face turning red. He struggled to say something appropriate, found he couldn’t, and then nodded again. Apparently satisfied with this, the woman returned her attention to the small display.

Mary did look different as a little girl, he thought.

She looked like the Mary I knew.

Little Girl Mary on her eleventh Christmas morning alr

eady had the long, black hair, already had the pale skin, but she had not yet lost the happy, carefree presence of the Young Woman Mary At Work.

In the photo, Little Girl Mary was tucking into a package of coloured pencils: the whole rainbow.

3

The sun was warm on Sycamore Drive as he ambled away from the opening act of Mary Townsend’s funeral. As he walked, his leather-soled shoes slipped on the dry, waxy tarmac, making a pleasant, sandy sound in the quiet day. At the entrance to the main road, Mr Ermey found his car. It didn’t look like it had been parked, however, but discarded. The windows were wound down, the front left tyre mounted the pavement, and the rear end was sticking out into the road. A feeling of total absent-mindedness overwhelmed him. It was a feeling he was no stranger to, but its familiarity was no comfort, indeed the sensation of having always forgotten something important was a hazy torment that seemed to follow him everywhere. Something crucial always lay just beyond his mental grasp, and no matter how hard he concentrated, it remained forever vague and unsettled. The counting helped, though, it helped him rein in his thoughts and keep them focused on the matter at hand. Screwing his eyes shut, his hands found the contents of his pockets, and he started to mutter and rap his fingers against his wallet once more.

“One.” Index.

“Two.” Middle.

“Three.” Ring.

He opened his eyes, but the car was still in disarray; if anything, it was the wake that now seemed like a dream. The car was just the car: a mess, but ultimately just there. He began to walk to the driver’s door, shaking his head in frustration.

You see, old man! You see this! Even now you can’t even remember a thing about it. This is proof of what happens if you don’t pay enough attention to the moment. What were you thinking about? Most likely too busy worrying about if you had enough deodorant on, or whether you’d dropped that painting.

He paused at the car door, his hand on the handle. This was no good. If he was to drive anywhere without causing an accident, he needed to focus. He needed to relax.

Mr Ermey's Funeral

Mr Ermey's Funeral