- Home

- Paul Roscoe

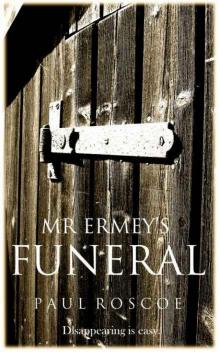

Mr Ermey's Funeral Page 7

Mr Ermey's Funeral Read online

Page 7

The figure stretched out his arms. From nowhere, more birds came.

Buddy looked at his joint; he’d heard that given enough weed, you could hallucinate, but it had never happened to him before. Maybe it’s the speed, he wondered. Maybe it had been cut with something else: drain cleaner, who knew?

Half expecting, half hoping the vision to disappear, Buddy blinked, but the figure stood its ground in the eye of the storm. Buddy opened his mouth to ask Lisa if she was getting all this, but she was still giggling.

The figure appeared to notice it was being watched, and it flew at Buddy, closing the distance between them in an instant. Buddy rocked back in his swing and his mind struggled to take in the basic truth of what was happening. Of what he was seeing.

The thing was made of birds.

Buddy watched slack-jawed, his hands to his face, examining their flight and the illusion it created. Two birds (they were called swallows, he remembered from somewhere) swooped together in impossible unison, linked wings, and spun 360 degrees before continuing their flight. This dance was replaced instantly by another pair swooping in to do exactly the same, and then another, and another – multiplied hundreds of times. The effect contrived to portray a humanoid shape, a fluttering illusion of a figure.

He looked up at the bird-thing through his fingers. It looked like a stick figure, the sort he used to draw in the corners of exercise books, making his own little animations by flicking the pages. In the space where its head should have been, a mass of swallows danced in a circle; the torso was no thicker than any of its limbs; its legs made an inverted ‘V’ that dangled from its crotch; and its arms were connected directly beneath the circular head in true stick figure fashion.

Its continual movement only added to the similarity: the jagged, disconnected judders from left to right, and up and down, matched his old, crude animations. In fact, the only real point of departure was the hands. Once in a while, Buddy’s cartoon men might have had a little ball to resemble a clench fist, but more often than not, his matchstick men were handless and fingerless. The bird-thing, however, had hands. Its fingers were swallows’ wings, opening and closing, slicing the air with their angular feathers, endlessly being replaced by more and more birds. To his horror, Buddy knew that these wings were in fact sharp, and that the clasping hand, with its mechanical relentlessness, could inflict a terrible amount of damage, no matter that it was just feather and bird.

He tried to say something to it, but his mind was numb with fright. He held his hands out to shield himself.

Oblivious, Lisa motioned for him to pass the smoke.

The joint smouldered in his fingers. Ash fell upon his trousers again. He passed her the smoke, carefully, slowly, not wishing to look around, but helpless not to.

Birds swooped across the lawn, catching flies and doing figures of eight; there were a lot, but the multitude he had witnessed had gone.

And – thank God, oh thank you God – the bird-thing had disappeared too.

In the distance he could hear a gate latch being shut, and the steady build of traffic.

He watched as Lisa smoked meditatively, and tried to forget what he had just seen.

*

“Why didn’t you just tell me there and then?”

The old storeroom was now thick with grey cigarette smoke. Dull green light still fell from above, streaking the walls. From outside, The General’s voice was an intermittent buzz. Buddy looked at her with a mixture of amusement and dismay. “What, me turn around and say ‘I’ve just seen a bunch of swallows that looked like a matchstick man. Here have a toke on this.’?”

He passed her an imaginary joint. Lisa looked down at his hand, as if contemplating accepting, but she said nothing.

Buddy shook his head and looked away. “I didn’t think I’d be telling you at all.”

“So why are you telling me now? What’s this got to do with Mary Townsend hanging herself?”

“I told you that I’ve been having these weird dreams all week, didn’t I?” he said. “Well, I reckon that because I wasn’t sleeping on Saturday, I sort of had a dream anyway. I guess that’s why he came to me like he did: in a hallucination, or whatever you want to call it. That’s the only way it makes sense – he knew I wasn’t going to bed that night, and so I wouldn’t dream about him. But he was coming whether I was dreaming or not.”

“So you’ve been dreaming about this…this bird-thing all week?”

“Sort of. I think the bird-thing is someone I used to know called David Hartman. The bird-thing only happened yesterday, but the dreams I’ve been having all week, they’ve really been about David, even though the only people in them have been the old gang, Alex, and Tom…”

“And Mary.”

Buddy shrugged. “And Mary.” He folded his hands around his knees and sat there silently, waiting for the inevitable question.

“So who was David Hartman?”

Buddy stared at the peeling paint on the wall, and as he watched, a leaf of paint fell away to the floor, coming to rest a little way behind a large box of exam papers, where it would remain, presumably, for the foreseeable future. I guess I won’t be the only one talking about this today, he thought, picturing Tom and Alex in the hall, their haunted faces. As he spoke, the words rang in his ears, feeling much too close:

“Back then, David Hartman was just a kid the same age as us, eleven years old. Only he went missing. They plastered his poster everywhere. He even made the TV news.”

“Did they ever find him?” Then quickly, already knowing the answer, she asked her real question, “His body, I mean. Did they ever find it?”

“No.”

Buddy reached for another cigarette, then paused; a glance at his wristwatch told him they had another half-hour at most before The General’s sheep would be herded back to the changing rooms. It would be enough.

“Back then, Lisa, just before David went missing…we did a terrible thing.”

He lit the cigarette, drew on it, and shook his head.

“No, scratch that, ” he said, cocking a thumb to his chest, the cigarette ember making a tiny smoke ring. “I did a terrible thing.”

Chapter Six

1

It was only when she pulled out her exam piece that she felt the first little wave wash over her. That was how she thought of grief – it came in little waves: some were larger than others, and some were smaller than others. Angela Welch, however, had yet to find herself in the way of anything tidal, and she was thankful for it.

She returned to her table near the window at the far end of the room, where she unfurled her drawing facedown and stared at its reverse. She resisted the urge to turn it over. Not yet, she told herself, wait until everyone is sitting down, then no one’ll notice. To bide her time, Angela pulled out her huge, white school bag and dumped it on top of her drawing; she unzipped it and pretended to rummage for pencils and things. All around, her classmates busied back to their places. Some were anxious to get on with their work, but most were full of the morning’s gossip, which bounced back and forth in subdued tones that failed to mask the undercurrent of gleeful excitement:

“I can’t believe she’s dead.”

“She never even left school – what a nightmare.”

“Her pictures are still up.”

“Well it’d be weird to take them down so soon. It’d look mean, wouldn’t it? Like she never existed or something.”

“I suppose so.”

I suppose so too, Angela thought.

The wave of grief swelled within her as she half-listened; she could feel it rising in her throat, almost reaching her eyes. It had an uncanny, surreal edge to it, something she had never felt for the passing of her grandmother.

Maybe this isn’t just grief. Maybe this is also some kind of shock.

She stopped searching through her bag and allowed things to gently fade away. Somewhere far off, her teacher walked into a room full of voices and started to say something, but it all blended

into one as her thoughts turned to her grandma.

Little waves rippled: the last visit to the hospital, the eventual news, the funeral, the detours she now took past the house she had visited so often as a child. All these things now surged forward. Angela wondered how bad things would get when her own parents died.

Silence brought her back. She lifted her head from her bag.

“Right, is everyone ready?”

Angela blinked, her eyes moist.

The teacher’s question met with mumbles of assent; Angela turned around to see Mr Ermey. He looked tired.

“Remember this is an exam situation, so the same rules apply. I want silence. The only difference being that if you need anything, just come over and see me. Please don’t call out or wait for me to see a raised hand.

“I know it’ll be hard to concentrate today, but please do. You have to. We’re struggling for time to get these pieces done before assessment. Any questions?”

Karl Jenkins, a quiet boy from Mary’s table, put a hand up.

“Yes Karl?”

“Will Mary’s work be assessed too?” His voice was hardly more than whisper.

Mr Ermey hunched forward over his desk, spreading his fingers upon a pile of untidy papers. He stared at the boy, his eyes sparkling with the possibility, and then he looked down, away. “I’m not entirely sure that’s possible,” he said. Then, slowly shaking his head, “No, Karl, I don’t think so. For one thing, this timed piece needed to be completed.” He looked over at the painting resting in the easel, the only one set up like that – everyone else was simply working at tables. “And besides, I very much doubt the examination board would accept a posthumous entry. I’ll look into it though, Karl, you can be sure of that.” The gaunt, greying teacher gazed around the room. “Anyone else?”

Silence.

“Okay.” Mr Ermey checked his watch. “Begin.”

The sound of quiet industry filled the room, amplifying the noises from outside: a teacher shouting somewhere; chairs shifting; lawnmowers humming; workers performing some unseen task. Angela slid her drawing out from beneath her bag, curled it into a tube, and left her place.

The room was an L shape that could begrudgingly accommodate two separate classes; however, the adjoining room was mainly left dormant, with no real evidence that it was ever occupied. It was into this secluded area that Angela beckoned Mr Ermey.

“What’s the problem, Angela?” Mr Ermey whispered, fiddling with a Sellotape dispenser.

Angela spread her work on a desk and turned it towards her Art teacher. Mr Ermey’s eyes grew wide.

Of the pupils who had not brought an object from home for their timed observational piece, Angela was one of the few who had resisted the stock cupboard’s easy charm of familiar bric-a-brac; familiar, that was, from every end-of-year presentation she had ever seen. Like Jenny Chadwick, who had chosen to paint her boyfriend, Matthew Reid; like Susan Mayhew who had chosen to draw her endlessly fascinating tie (Angela was sure it was something like the third time this year that Sue had either drawn or painted her school tie); and like Mary Townsend who had chosen to paint the world beyond the window, Angela had chosen to depict an element of her surroundings. In her case, it was the window itself, the radiator below it, and some other bits of furniture: a table supporting an old sewing machine and an erected easel supporting a work-in-progress.

Angela’s drawing also contained the pupil who had been working at the easel.

Even at this stage, Mary was instantly recognisable. Angela found figures easier to do from the back, and she had caught the proportions of her subject’s frame with no difficulty at all. She had captured Mary in action: her body leaning forward, the brush in contact with the canvas; and although the detailed shading of Mary’s clothing was yet to be done, she had worked in its essential crease lines.

“You’ve not started to draw her painting,” Mr Ermey said, pointing at the outline of the easel.

“No, I thought it best to get the figure done first, Sir.”

“Good thinking, figures are difficult. You’re doing well, Angela. I am, however, worried at how complicated this piece is. There’s a lot of detail to get through, and you mustn’t neglect the floor or the ceiling either.”

Angela nodded and looked at her teacher; his eyes remained lost in her drawing.

“Should I rub Mary out?”

Mr Ermey looked horrified but quickly concealed it; this he did by scratching his chin, which, she noticed for the first time, was covered in a bright red shaving rash. It looked painful.

“What on earth would you want to do that for?” he whispered, his voice wavering a little.

Angela opened her mouth and, beyond stating the obvious, didn’t know what to say.

“Anyway, if you did that,” he continued, “there would probably be a nasty mess right here.” He pointed at the fastened bows in Mary’s apron strings. “These lines seem pretty deep, and they’ll probably show through anything you draw over it. You know you shouldn’t press down so hard, Angela, choose a softer pencil if you want to make a darker line.” He tapped the painting. “But that’s not the only reason for continuing with it the way it is, Angela. I think you’re doing a good job. This is a timed piece, and here, well, you’ve captured time itself.” He pushed the sheet back towards her. “Time itself,” he repeated, looking back towards the classroom.

Angela began to curl up the paper.

“If I were you, I’d finish the easel this morning. I’m not in any rush to remove it right away, but I will be removing Mary’s pieces over the course of the day. I don’t want to seem cruel, but they could attract the wrong sort of attention.”

She wondered what sort of attention he meant, but did not ask. Mr Ermey placed the Sellotape dispenser on the table, then folded his arms behind his back and raised his chin. With some dismay, Angela noted that this was his ‘waxing lyrical’ posture, the one he adopted when weaving through the tables and going off on tangents, disturbing what would otherwise be a pleasant session. The tube of paper in her hands began to feel big and heavy.

“I appreciate your sensitivity regarding this, Angela, and if you still want to remove this aspect of your picture, well, it’s your work when all’s said and done. However, if you choose to keep and develop it, then I will take responsibility for the decision, and I will tell anyone who cares to listen why I encouraged you to do so. People need to be aware that Art is not instantaneous, but that it spreads and grows and develops over time. Indeed, Art can only be through time, because it is essentially of time itself.” Then, with a small smirk, he added, “Art is a very timely thing, Angela.”

Inside Angela, clocks began ticking, and standing itself was becoming uncomfortable. “Thanks, Sir.” She started towards the other room.

“Angela?”

“Sir?”

“Have you…er…”

“Decided?”

He nodded.

“I’m going to carry on with it as it is.” Angela shifted in place, her feet anxious to be moving. “The figure’s pretty much there. I can remember the rest.”

“That’s good.”

She moved slowly as if to go, and was halted once more. This time her teacher held up a hand to indicate that he had something else to say.

Here it comes. He hadn’t asked the most obvious question yet, and for a moment there, she thought he wasn’t going to.

“Angela, did she know you were drawing her? Did you discuss it together?”

Angela examined the face of the man asking her this question, and realised she had never really looked at it before. It was the face of a young man buried beneath the trappings of an older one: eyebrows that once had been contoured and shaped now sprouted wiry strands of platinum that curled off at unlikely angles; cheeks that might once had been rounded and soft were now hollow with leathery, speckled skin; and hair that once had been dark and flowing now gathered in two clumps of dull grey. Only the eyes had managed to survive the metamorphosis intact:

they sparkled with feverish intelligence. Angela found it impossible, however, to imagine that they had ever sparkled with real happiness. Indeed, what she had long mistaken for Mr Ermey’s bad case of the usual teacher contempt – a more pronounced version of the general weary countenance worn by most of St Vincent’s staff – was really a sort of coldness. It was as if he was turning her over in his mind, making comparisons and estimations, developing theories. He’s an Art teacher, that’s all, she told herself. To him, everything is a potential subject, including his pupils. The idea made sense, but did not comfort.

“We didn’t discuss it, Sir, but I think she knew I was drawing her.”

Mr Ermey stared at the rolled up drawing in her hand. “And how do you think she knew that?”

Angela gazed towards the other room, summoning the memory of last Thursday’s session. It had been another bright, sunny day. She could picture Mary in front of the window, working; she saw the way she moved, the way her head turned.

“She looked at me, Sir.”

Mr Ermey arched his left eyebrow.

“I know we weren’t really friends, so I felt weird mentioning the drawing to her.” Angela felt herself rocking on her heels and stopped. “But honestly, I don’t think she minded. She could definitely tell I was drawing her.”

It was better than that, but she didn’t know why. She was sure that Mary not only knew that she was having her portrait taken, but that she was happy with the idea. There was something about the way she would move…

Understanding gripped her:

It was every time I looked away, that was the thing!

The image came to her vivid and breathing. She would be staring at Mary’s back, either getting the contours of her body just right, or investing more and more time into the ties and folds of those tricky apron strings, and Mary would be engrossed in her own work, seemingly oblivious to her classmate’s watchful scrutiny. At the time, Angela had just considered herself lucky that her one moving subject tended to be in the right position long enough for her to get down the detail she needed.

Mr Ermey's Funeral

Mr Ermey's Funeral