- Home

- Paul Roscoe

Mr Ermey's Funeral Page 9

Mr Ermey's Funeral Read online

Page 9

“Come with me,” David said, standing up.

Tom found some strength in his legs and accompanied David as he walked over to the school buildings.

David trotted up the stairs and turned to Tom. “Do you remember doing this?” He proceeded to sidle out onto the small, brick ledge that ran beneath the windows.

“Of course. We did it all the time.” Tom followed David along the windows as the playground sloped away beneath them. Soon they were peering into the girls’ toilets. Tom noticed that the mottled glass in the stall had been changed to a clear pane, and instead of a cistern and bowl, there was a bed, strewn with pills, spent bubble strips, and an empty glass. The toilets were dark, and not really toilets at all; where the door leading out into the main corridor should have been, a yellow curtain billowed. The curtain in his own bedroom.

Curled beneath the sheets, the body lay terribly still.

“Is that me?”

David’s smile was not without pity. “Yes, Tom. Yes it is.”

5

Tom opened his eyes.

In the twilight came a crash of wings.

Chapter Seven

1

Mr Ermey opened his eyes.

Automatically, he began to play with the key ring – rubbing it helped him think. It was in the shape of a cartoon Volkswagen Beetle: two humps for the roof and bonnet, two eyes for headlights, and a smiling bumper. It had once been painted red, with his first name printed on a tab underneath, but the enamel had worn away years ago. Mr Ermey dropped his hand from the ignition and gazed around his car’s cream interior. A half-smoked pack of Marlboros poked out of the dashboard, squeezed into a narrow space just below the cassette player. He reached in the glove compartment for his lighter, but then thought otherwise – he didn’t want ash on his suit. And besides, wasn’t he supposed to be giving up? He glanced over his shoulder towards Sycamore Drive, checking for signs of the funeral party. He supposed he should be going. Leaving the funeral proceedings already looked bad, but then to be spotted loafing would look much worse, especially to the headmaster.

You still have time to go back, you know. You’ve hardly been gone any time at all – no one will have missed you.

He wiped his forehead with the back of his wrist, the thick cuff mopping his sweat. His neck itched. He pictured St Vincent’s church, its endless drive covered in a confetti of pink cherry blossom, and saw himself in a train of cars crawling along, inexorably drawn upwards and onwards to the inevitable emotional explosion.

No, old man. They might make it today, and you’ve got to be home for that.

Mr Ermey fastened his seat belt, switched the ignition, and put the car into gear. His tyre left the kerb with a thud as he finally rolled away from Mary Townsend’s funeral.

2

Like all the houses in the nearby estates, Mr Ermey’s house on Richmond Avenue was stone clad and surrounded by small strips of land made semi-private by foliage of one sort or another. As he approached the open gate to his driveway, he noticed something small and white protruding from the hedge at the bottom of his front garden and slowed the car to get a better look. It was a polystyrene tray, the remains of a meal purchased from the local fast food place, Mario’s, a do-it-all establishment that sold pizzas, burgers and fried chicken. Mr Ermey cursed the individual that had treated his hedge as a litter bin and snapped his head around scanning the empty pavements for the culprit. Cursing once more, he reversed into the drive, gravel spitting and crunching beneath his wheels.

He killed the engine, got out, and cursed once more.

“The dirty little…”

He stared at the car door handle, and that same absent-mindedness he had felt when he found his car abandoned just off Sycamore Drive this morning now washed over him again. He pulled the handle and found the door already locked. He patted the keys that had found their way into his left trouser pocket (and checked his wallet for good measure) and tried to remember locking the door.

He couldn’t.

Mr Ermey rubbed his chin, accidentally agitating the tender rash that was still sore. He walked around to the passenger side, unlocked the door, removed his Marlboros and lighter, pocketed them, and relocked the door. This time he focused, doing the job right. He watched himself turn the key, felt the mechanism resist then encourage in its familiar way. Good.

“One,” he whispered, gripping the key tightly.

“Two.” Tighter.

“Three.” He dragged the key from the lock, sensing the little levers springing back into place as it retracted. To Mr Ermey, this sensation was both essential and troublesome. On the one hand, the tactile feedback communicated the fact that he had really locked the door – the faint dragging vibration flowing from car to key to hand confirmed this; but on the other hand, the removal of the key spelled the end of this reassurance and, once removed, there was a space once again for doubt.

At this point, he thought, a more inexperienced person might simply replace the key and start again. But no, not I. I’m past all that.

Instead, he slid a finger up the passenger window to the seal, making sure the window was wound tight, and gave the door handle another tug.

“One.”

Then he did the same for the rear door.

“Two.”

He then tugged at the boot and ran his finger down the edge where it met the main body of the car.

“Three.”

Then he checked the other rear door.

“Four.”

Mr Ermey returned to the driver door again, but this time he fingered the window and gave the handle five small tugs, counting each one. On “Five,” he let go, then lay his hand on the car’s roof. It was hot and felt gritty, badly in need of a trip to the car wash. As he rapped his ring, middle and index fingers he counted his usual final flourish, “One-two, one-two, one, two, three.” On the three he pushed away from the car and pushed it from his his mind, turning quickly to head out of the drive before the whole process started again.

The polystyrene tray floated in the green hedge. It was folded, snapped in two, and speared with a small plastic fork. Ketchup dribbles smeared the leaves. Mr Ermey delicately pinched the litter sculpture between a forefinger and thumb and extracted it; his free hand rearranged the leaves, fluffing them back into position. Stooping, he checked that no peephole was remaining where the litter had been, then he returned to the drive. Deliberately averting his eyes from his car to avoid the temptation to check it again, he cast his gaze across to the view of the local hillside. Refocusing helped.

He entered his back garden, whereupon he deposited the polystyrene sandwich in a green wheelie bin. The garden was a modest patch of grass in need of mowing, lined by evergreen trees and bushes in varying states of tidiness. In the centre of the lawn stood a greying wooden bird table, empty save for a scattering of pink pellets and a saucer containing stale and dirty water.

Mr Ermey took the saucer, tossed the water, and went inside.

3

Fifteen minutes later Mr Ermey emerged wearing brown chinos and a white shirt, his mourning-wear hung neatly in the bedroom. He was carrying a mug of coffee and a saucer of fresh water; he positioned the saucer in the centre of the bird table, set his coffee on the lawn, then went about dusting off some patio furniture: a chair and table – once white and gleaming, now grey and chalky. He emptied his pockets on the table – a Zippo and his cigarettes – grabbed his coffee and sat down.

With a click, chink, snap, blue smoke twirled in the morning air.

Sitting there, relaxing in the stillness of his garden and the growing heat, he could almost pretend he’d been home all morning. Mr Ermey looked out into the brilliant midday sky, and let his gaze follow the line of conifers; he kept as still as possible, waiting for the birds to arrive. Eventually they would. They knew him well enough, especially the blackbirds and the one robin that seemed to not mind his company. Already he could see two blackbirds arguing in the branches of his neighbour’s elm.

Come on... Come on...

The two birds grew still, as if hearing the thoughts of the wiry old man, and then both flew off, one after the other. The trees flattened against the blue sky, and went darker, creating an outline. Colours at the periphery of Mr Ermey’s vision started to drain, turning into a sepia tunnel. The tree looked further away than it was. Mr Ermey rubbed his eyes and yawned, then gulped more hot coffee, feeling it burn down his chest but not caring. He stubbed out his cigarette and got up, his knees popping and cracking. I’m getting too old, he thought, and a grim smile stretched across his lips. Too old to teach, too old to move. And at that he caught himself, as he had done at the car door, and he stared into the distance. The feeling of having forgotten something was strong and uncanny, like a reverse dejá vú.

Come on Ermey, what was it?

He let it go. If it wanted to, it would come back.

Mr Ermey yawned again, and stretched, purposefully making his chest crack. It was an old habit, and a bad one, but he was helpless not to enjoy the unique sensation of his rib cage threatening to bust open. He scooped up his smoking kit with one liver-spotted hand, picked up his empty coffee mug with the other, and went inside. He dumped the mug in a fresh bowl of suds – the sharp smell of lemon detergent filling the kitchen – and stood at the back window, looking out into the garden.

The robin was on the table, pecking a pellet; now it was gone, back to the trees. Mr Ermey saw a blackbird peering down from the elm, now another – the same ones, no doubt. He ducked into the dining room, caught his leg on the table with enough force to leave a bruise that would take at least a month to fade, and removed two items from a high shelf, carrying them back into the kitchen, limping slightly as he did. In less than a minute a mini-tripod was set up on the kitchen table that ran beneath the window, and he was in the final stage of attaching a zoom lens to the camera that sat on top. That done, he found the usual position, set the focus, and waited. It wasn’t long before the two birds swooped down to the table and nuzzled their beaks in the pink matter.

Mr Ermey took four shots of them and then locked the back door – checking the handle with a brisk count-check. Before he could check the lock again, he escaped to the dining room and closed the connecting door. He stood with his hand resting on the handle, staring at the biscuit tin in the centre of the dining room table. “There are strategies, and there are schemes, but sometimes it’s best just to get the hell out,” he said as he lifted the lid and took out a plain chocolate digestive. He sighed and ate.

Home at last.

But where have I been? Oh yes, that’s right…

Brushing crumbs from his hands, he sauntered into the small, downstairs bathroom and urinated without bothering to close the door behind him. Washing his hands, his thoughts turned to Mary’s funeral, and he now felt a sour regret at not staying for the whole service. Following the regret came a mixture of dread and guilt as he pictured himself apologising to Mr Makinson. He supposed he should really get a bite and get back to school, the lunch hour was fast approaching and he had a million jobs to do, not least the clearing out of the previous year’s coursework.

Don’t you mean the year before, and the year before that?

Yes, yes he did. Getting rid of old artwork was something he hated. Even the rubbish – it all seemed like such a waste. But there would soon be another year’s worth to store, and there simply was no more room. He thought of the heap of paintings piled up in the corner of his stockroom and wondered if the Townsends would ever claim Mary’s bits and pieces.

They had only one piece on display at the wake. One. And which one was it?

Mr Ermey stared at the mirror and watched the growing expression of alarm on his face. Suddenly he was quite sure that the Townsends would not be at all concerned about the artwork in his possession.

It was the last thing she ever did, wasn’t it? That was why it had pride of place on the mantel. They had found her hanging in her garage...and I bet they also found that hanging somewhere nearby. Maybe in her easel.

What little appetite he had left him.

Was that it? Did they think the painting was some kind of suicide note?

Of course they did, wouldn’t you?

Mr Ermey washed his hands and dried them by running them through his hair, feeling the uneven contours of his scalp.

A painting of the old shelter for a suicide note. But not just a painting of the old shelter – this one was haunted by four ghosts: a yellow jacket, a football, a cigarette, and a bicycle.

His mind adrift on the memory of Mary’s brushstrokes, he walked into the living room and lifted the telephone receiver. He punched a speed dial button, heard a female voice announce the name of the school he worked at, and then heard himself start to speak.

“Jo? Ermey. I won’t be coming back this afternoon. No, I’m sick. Yes, Jeff’s at the funeral, but I can’t tell him myself, I’ve gone home. Well, that’s what I’m trying to tell you, I’m sick. I’m not coming in this afternoon. That’s right, I went to the Townsend’s house for the wake, felt sick, came home. I didn’t go to the actual funeral. No, I haven’t a clue – maybe a virus. I’ve only got the one class. That’s right, it’s all written down in my folder. No, anyone’ll do. Thanks. Yes, I’ll do that. Bye.”

He set the receiver back in its cradle and turned to an room that was usually cosy, but today only felt like an arbitrary collection of things: a three piece suite, a Hi-Fi, a TV, a cabinet of porcelain birds, and a coffee table. It could be anyone’s place. He couldn’t even remember picking out the wallpaper – an embossed circular pattern that just repeated, repeated, repeated. He stared at the three-piece suite like it was a family of strange, exotic animals.

Why a three piece suite? Why not just a couch, or even just a chair? Who the hell was I expecting to visit me?

He returned to the dining room and sat in one of the uncomfortable chairs, and became aware of the table’s size for the first time in a long time. The man in the showroom had talked up this fancy circular one with the high polish finish and the fussy edging, and he’d had money to spare. It dwarfed the room. It had to be pulled away from the wall if he was entertaining, and then there was hardly any space left in the room itself.

His right thigh throbbed and he rubbed it, now realising that the table was indeed pulled out.

When did I...?

His fingers probed his scalp once more, pulling his hair. With tremendous effort, he unclenched his fists and spread them on the table – a table complete with cutlery and placemats that he had absolutely no recollection of setting.

It doesn’t matter, he told himself. Like abandoning the car with its windows open, it doesn’t matter. It’s just further proof that all this checking and double-checking and triple checking upon checking is just nonsense. Irrational, pointless nonsense.

He considered pushing the table back to its normal place, then decided against it. In a way, it’s kind of nice like this, like a family might be ready to sit down any minute.

He smiled. He guessed it was sort of fun to pretend. He surveyed the empty seats and guilt shivered through him as he imagined the school carrying on without him whilst he played imaginary tea parties.

Never mind, when it comes to guilt, you’re an old hand.

“Yes, that’s right,” Mr Ermey said to the chair opposite, “a very old hand. More tea?” He grinned as he lifted an invisible teapot and poured fresh air into the water glass. As he set it down, it came to him that Mary would be buried by now.

His one star pupil in a grave.

And what will become of it? People think graves last forever, but they don’t. St Vincent’s is one of the oldest churches in this area, but even its gravestones only date back a few hundred years or so, not much more. The oldest ones are illegible, just confused carvings lost to water, air, and time. If a graveyard is testament to anything, it’s that the past is a thing forgotten no matter how hard we try to remember it.

Mr Ermey stared a

t the small mat before him that protected the table’s highly polished finish. It had an illustration he had never really cared for, of some children playing in a barn, with a decorative border of tiny hay bales and pitchforks. He picked it up and examined it: a rectangle of chipboard, coated with a layer of hard plastic, and a thin cork sheet underneath. He brushed salt grains with his thumb. This will probably outlast Mary’s grave, he thought. Donated to a charity shop, bought, used, and either sold again or shoved in an attic somewhere and forgotten about. Whichever way, chances are it’ll be kept away from the elements, and unlike churches and graveyards, its destruction will never be rationalised in a new housing estate or motorway planning agreement. He set it back down on the table and stared at it. As he did, dread turned his stomach to iron.

Something was wrong. The design was wrong.

His first impulse was to turn it around, but he knew that that wasn’t the problem at all. Mr Ermey made a sound of utter exhaustion, like the air was being sucked out of his lungs.

Mr Ermey saw the placemat, certainly. But now, staring hard, he thought he really saw it. This was worse than the car, though, and worse than the table. Much worse. He squeezed his eyes shut, trying to change reality, but it lingered on in an afterimage that burned in the reddened darkness.

Laid beneath the protective lacquer, and bonded to the hard plastic coating underneath, was Mary’s painting of the old shelter.

The figures, however, were complete.

Chapter Eight

1

The sky over Bracton Hill was deep and heavy and dark; the girl lifted her chin to it and breathed deeply. From peak to valley, the fields were covered with a delicate, unbroken sheen of water. At the top, the wind’s steady scrape against the beacon was the only sound to be heard.

As the sun pierced the indigo horizon, miniscule factories appeared, standing smokeless in the distance. White pinheads chased orange pinheads across the murky land, and lakes glimmered in the twilight like slivers of foil. The land sank as the sun rose.

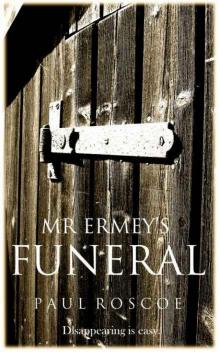

Mr Ermey's Funeral

Mr Ermey's Funeral